COAL MINING IN SCOTLAND

Background to Coal Mining in Medieval Scotland

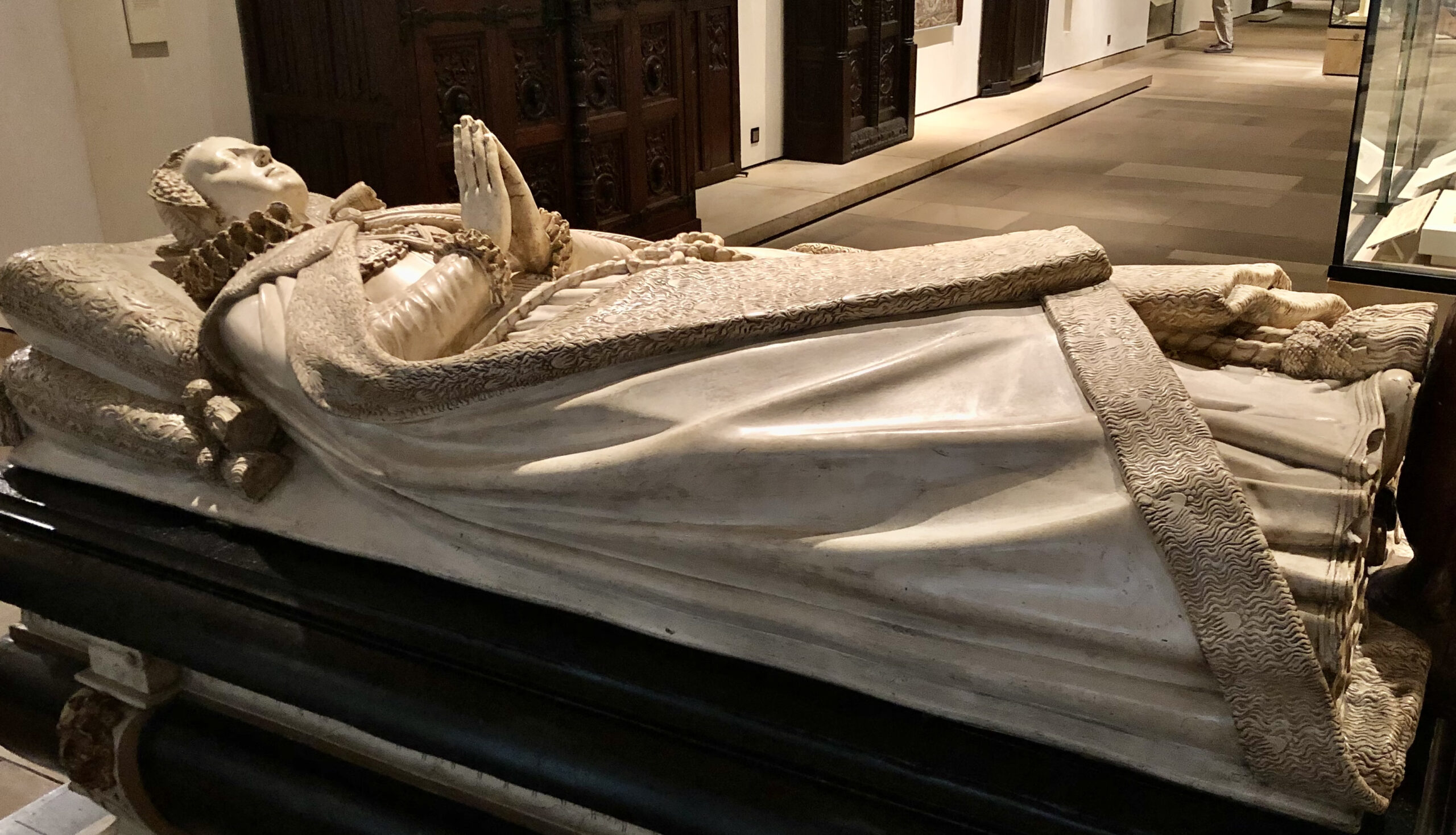

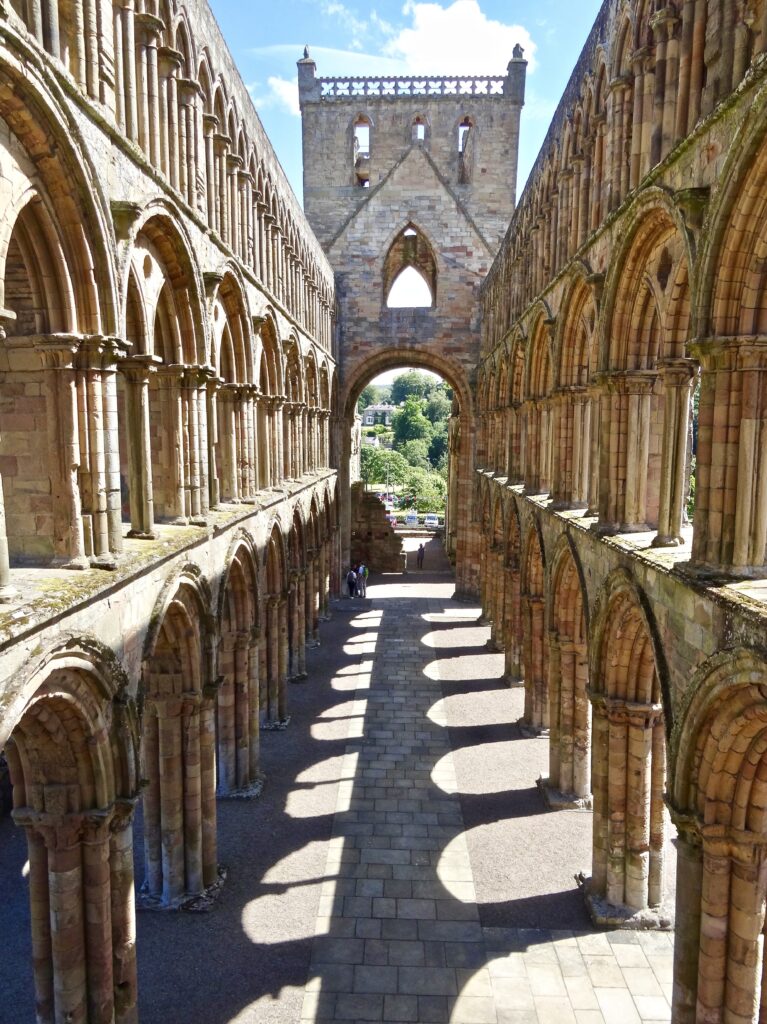

The history of coal mining in Scotland can be traced back hundreds of years. Numerous coal mines were created throughout the central belt of Scotland, predominantly in the Lothians, Fife and Kilmarnock. However, the earliest coal mining can be traced back to the Cistercian monks who had settled in various parts of Scotland. However, two monasteries in particular, Newbattle in Midlothian and Culross in Fife are recorded as being among the earliest coal mines.

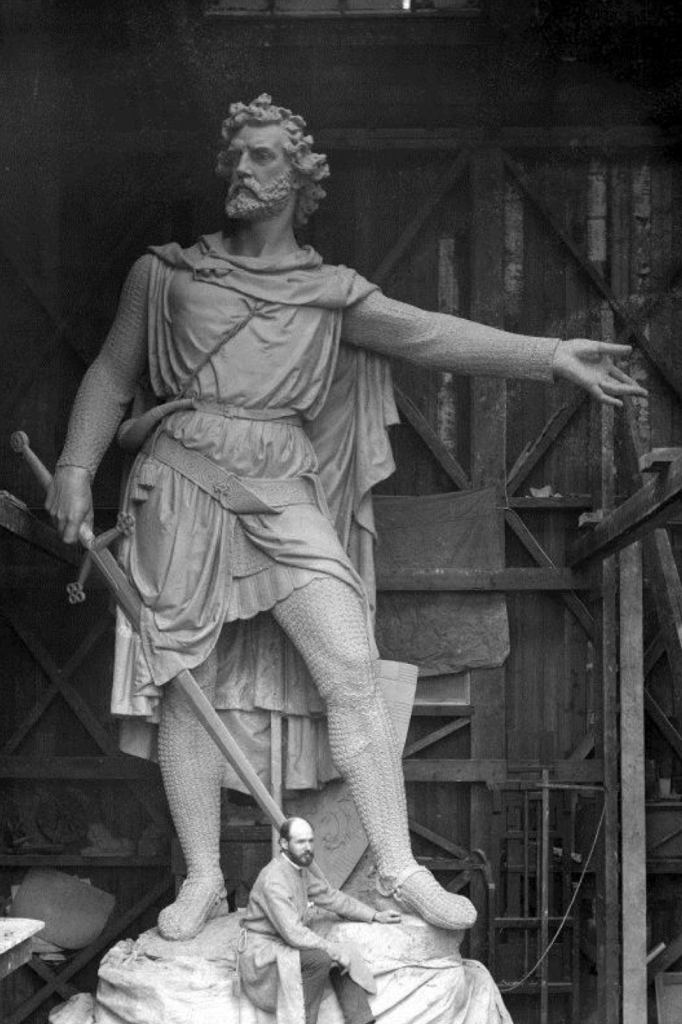

The monks can be credited with the key which would unlock the future prosperity of Newbattle and Culross through coal mining. During this period, early travellers wrote with awe when they came across the “black stones which burned.” Sadly, for the monks their coal mining business was limited by how deep that they could dig. But this problem would be solved by one man in the mid to late 16th century. His name was Sir George Bruce, reputedly a descendant of King Robert the Bruce.

He was granted the lease of Culross Abbey’s collieries. Thanks to technical experience he acquired whilst travelling through Europe, he was able to continue where the monks had left off. Three of the major obstacles in coal mining which had defeated the monks was the limited depth that they could dig to, poor ventilation and poor drainage. Where the monks had only been able to dig to a depth of 30 feet, his various innovations overcame these obstacles and allowed coal mining to a depth of 240 feet.

By 1625, his coal shafts stretched over a mile out below the Firth of Forth. Without his innovations this would have been impossible. He even took advantage of a small tidal island in the middle of the Firth of Forth. He had a circular brick wall built around it complemented with a jetty which allowed ships to dock alongside before taking their cargo to Europe. The success of Bruce’s mine was to be seriously damaged in the March of 1625 because of one of the worst storms that the country had experienced. A year later Bruce died and his coal mine with him. It was at this point that coal mines in other areas expanded their operations.

Background to Coal Mining in Victorian Scotland

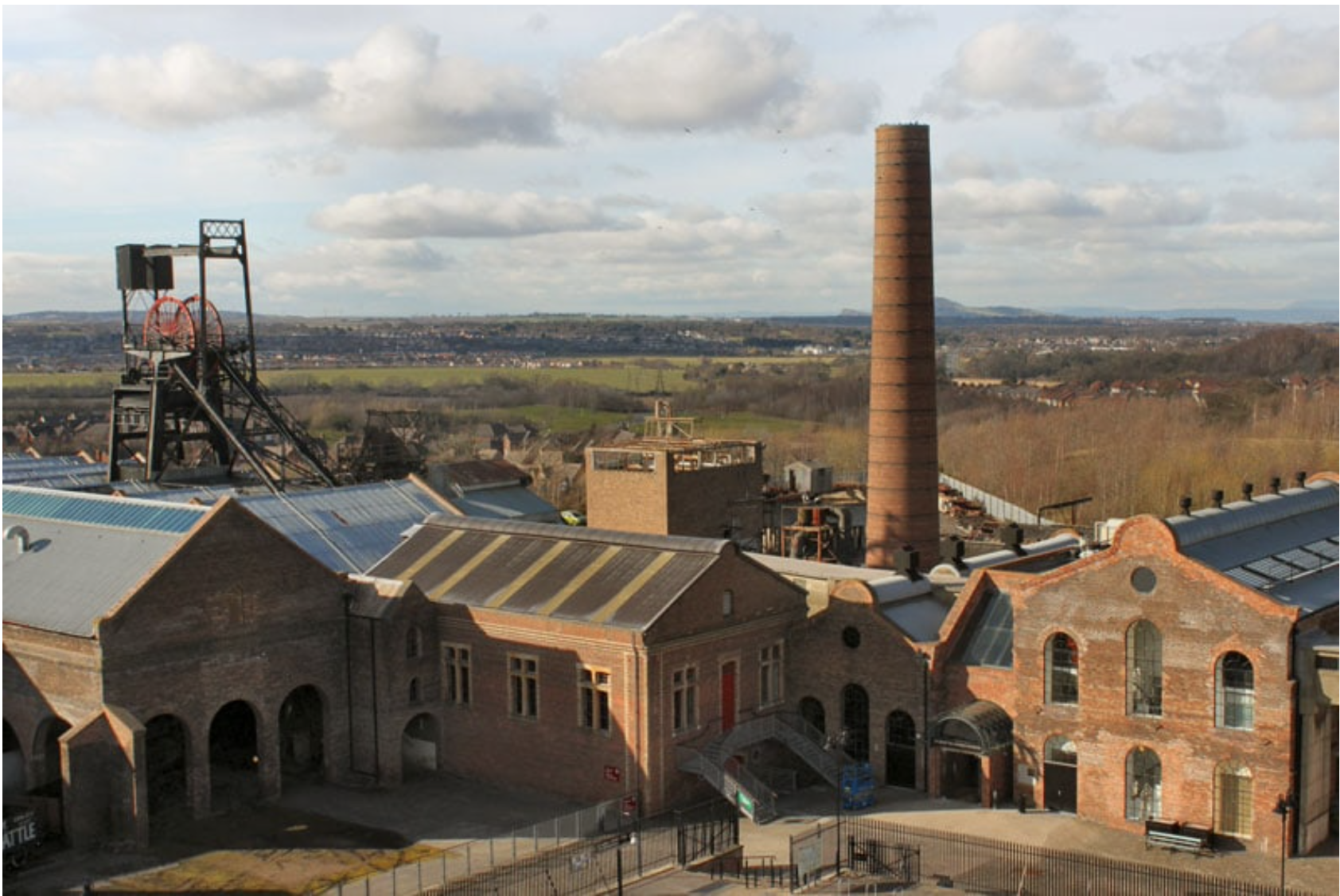

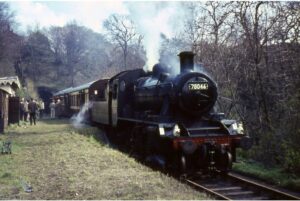

Fortunately for visitors, less than ten miles south of Edinburgh, we are fortunate to have a first-class resource at the National Mining Museum Scotland. The former Victorian “superpit” – the Lady Victoria Colliery has been preserved and is open to the public for both guided and self-guided visits. It really opens your eyes to the hard lives endured by miners and highlights the history of coal mining in the area, right back to the time of the monks at Newbattle Abbey.

In many respects, like Culross, coal mining was initially carried out by the monks of Newbattle Abbey nearby. But over time, the monks would rent or lease out the land to wealthy lords who would then provide their own workforce to work the mines. Over the subsequent centuries the landowners began to develop huge coal mines on their land. As had been already proven by George Bruce in Culross, it was potentially a lucrative business. With cheap labour came big profits. Until 1842, mines were run almost like slave plantations with the people who lived on the land being employed by the landowners to work down the pits. Whole families would be employed in coal mining.

Children’s Employment Commission

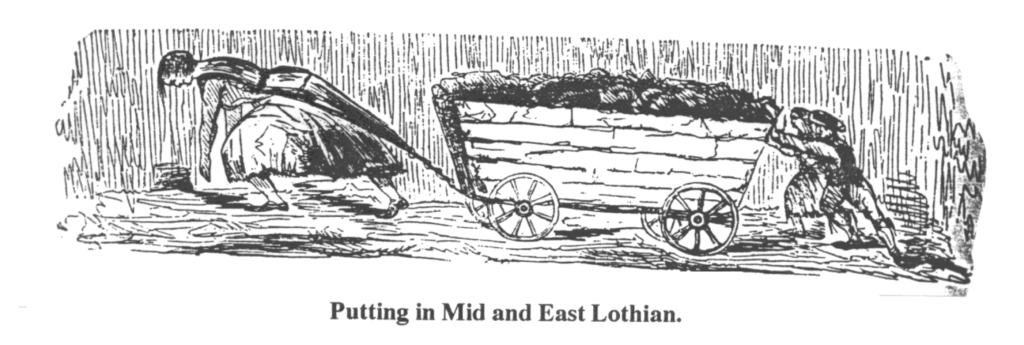

As a result of the three-year investigation into working conditions in mines and factories in the four nations of the United Kingdom, the Report of the Children’s Employment Commission was published in 1842. It consisted of thousands of pages of interviews with children as young as five who were actually employed to work in the coal mines. Why such young children were employed is very much down to the fact that industrialisation was expanding at pace. Children, on average, were five times cheaper to employ than an adult, yet were expected to work the same hours. In coal mining that could mean 14-hour shifts. The youngest and smallest children were used to climb into the confined spaces of machinery in order to clear a jam. This was commonplace in the mills but also took place in the coal mines.

Page after page of discussions and interviews with children who were employed in the coal mines make for dismal reading. This report finally lifted the lid on the working and living conditions of young children perpetuated by the very landowners and industrialists of the day. It couldn’t have come as a shock to them, but it certainly did to those who had no inkling of how coal was mined and how it was brought to market. Here is just one account from an eleven-year-old boy.

William Kerr, 11 years old, coal-bearer:

Wrought below five years. Goes down at five in morning, returns six and seven at night. Gets my bread as other laddies do. Carries coal on my back. Can fill a basket of 5cwt. in six journeys. It is 150 fathoms from father’s room to pit bottom. I am o’er sair gone at times, as the hours are so long and the work gal sair. Never have the opportunity to get some sleep.

Sadly, parents had no choice but to put their children to work in the mines as this was what their employers expected. Generally, most mine owners provided accommodation for their workers which they paid for from their wages. Owners expected generation after generation to be employed in their mines. Girls who also worked in the mine would fall pregnant at the earliest opportunity to escape the horrors of the mine. They would go on to have many children. It was not uncommon for there to be twelve children and more in a family, all of them eventually being employed in the mine. Having worked long 12-14 hour shifts, they would return to their pitiful one-room cottage, where they would hopefully get something warm to eat. Then they would collapse into a deep sleep before doing it all again.

So What Changed?

What you may ask changed as a result of the Commission Report? You may be surprised to learn that actually not a lot changed. The Mines and Collieries Act 1842 passed by Parliament, prohibited all underground work for women and girls and boys younger than age 10! Not surprisingly the Act was watered down with amendments when it reached the House of Lords. A number of the Lords were either coal mine owners or had vested interests in them. Similar attempts to delay were made when the Abolition of Slavery Act was put before Parliament in the late 1700s. In 1887 the minimum age for boys to be able to work underground was raised to twelve. And it wasn’t until 1900 that another Act was passed that raised the age of employment for boys from twelve to thirteen.

As time went on further legislation was enacted to improve the safety of workers working underground. Furthermore, a limit was imposed on the number of hours that miners could work under ground to 8 hours in every 24-hour period. In 1912 after the national coal strike had lasted 37 days, the Coal Mines Act was passed which established a minimum wage for the first time.

The Establishment of the Lady Victoria Colliery

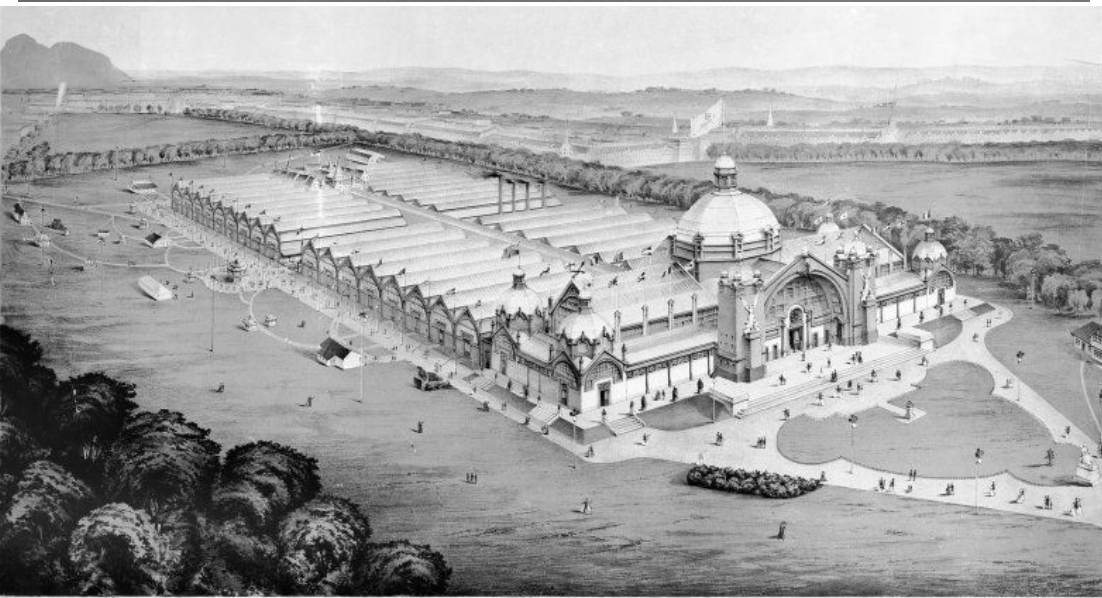

It was during this period of change that the Lady Victoria Colliery became established. Thanks to an amalgamation of the Marquess of Lothian’s coal company and that of Archibald Hood, the Lady Victoria was established. It operated from its opening in 1895 until its eventual closure in 1981. At its inception in 1895 it was the largest colliery in the county of Midlothian.

Hood who had already worked in the South Wales collieries, brought his considerable expertise to bear at the Lady Victoria. Not only did he want to improve working conditions for his workforce, but he also wanted to improve their living conditions. The rows of miners’ properties still exist to this day with their own little plot of garden and are a testament to their construction.

The Lady Victoria’s location was chosen to exploit the type of coal that could be mined in the area. They were called “Parrot” and “Splint” coals and were in high demand. But it meant that the shaft had to be sunk to a greater depth than previous worked coal seams. This meant sinking to a depth of in excess of 400 metres. In fact, the Lady Victoria shaft was eventually sunk to a depth of 510 metres

Boom Period of the Mid-20th Century

Over time, thanks to improvements in technology, chain-type cutters increased the volume of coal that could be extracted. These were then replaced by shearer loaders along with armoured conveyors that were used to transport the coal from the coal face. In the same year that the colliery was nationalised, it produced the equivalent of 1,246 tons of coal per day. By 1951 it was producing 2,000 tons per day. With increased mechanisation it resulted in a reduced workforce together with less hard manual labour.

By the 1970s the Lady Victoria had been superceded in scale by two other collieries in Midlothian, namely Bilston Glen and Monktonhall who had workforces of 2,150 and 1,600 respectively. In total there were thirteen operational collieries in Midlothian and that was just one county. By the time the Lady Victoria closed in 1981, 87 years after it had opened, it had produced almost 40 million tons of coal.

Nationalisation of the Coal Mines

In 1947, there were 20 collieries, but they were taken into state ownership and came under the umbrella title of the National Coal Board. It meant an improvement in conditions, wages and Trade Union rights. In the early years of nationalisation, it was a fairly prosperous period for the coal mining industry. Sadly, though decline began to set in, and by 1984 Midlothian was the scene of some of the most acrimonious action by the miners’ strike. Although the Lady Victoria Colliery, now the National Mining Museum Scotland, closed in 1981, Bilston Glen managed to last out until 1989 and Monktonhall until 1997. Both sites were demolished not long after their closure. Now you cannot find a single trace of either. You would never be able to tell that a coal mine had been in operation at either location.

National Mining Museum of Scotland

Despite this, however, we are fortunate that the Lady Victoria Colliery was preserved. Thanks to Historic Scotland, now titled Historic Environment Scotland, the entire colliery was categorised as a List ‘A’ building. It can lay claim to being one of the best-preserved Victorian collieries in Europe. In fact, on the day that I visited the colliery, a Polish film crew were there filming for a documentary that they were putting together.

Although the site in total covers four acres, the public area occupies a smaller proportion of the overall site. Thanks to funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, the European Regional Development Fund and Historic Scotland, it has become a popular visitor attraction for visitors staying in Edinburgh. It is also a place of learning for youngsters living in the Midlothian who can learn about the history of this area.

Although some areas of the colliery are in a derelict state, thanks to a Scottish Government-funded conservation project in 2009 many of the vital working areas have been preserved. In addition, the more exposed parts of the colliery have been made more resistant to the elements. With the work that has thus far been carried out, it now makes many parts of the colliery more accessible for visiting groups.

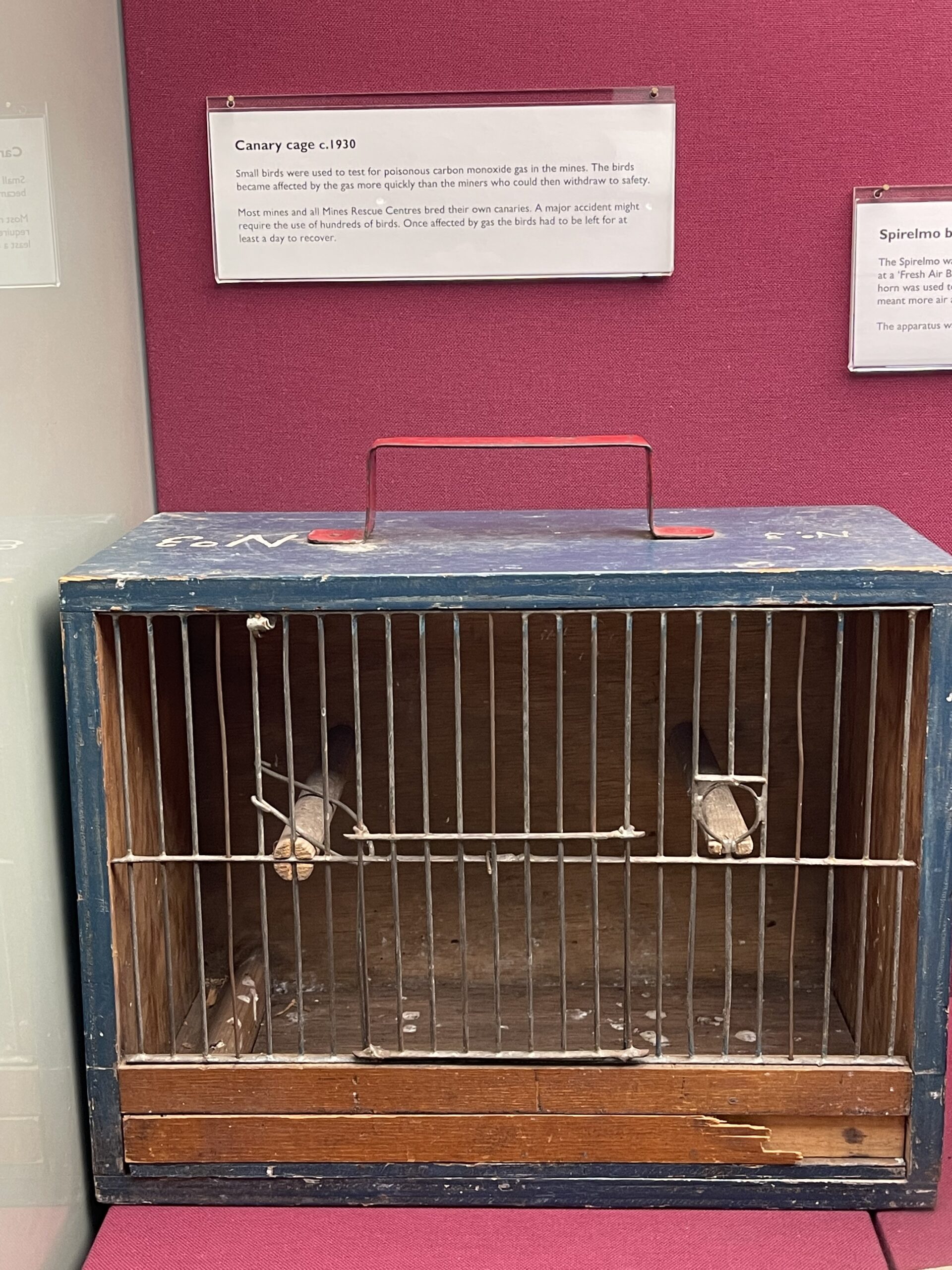

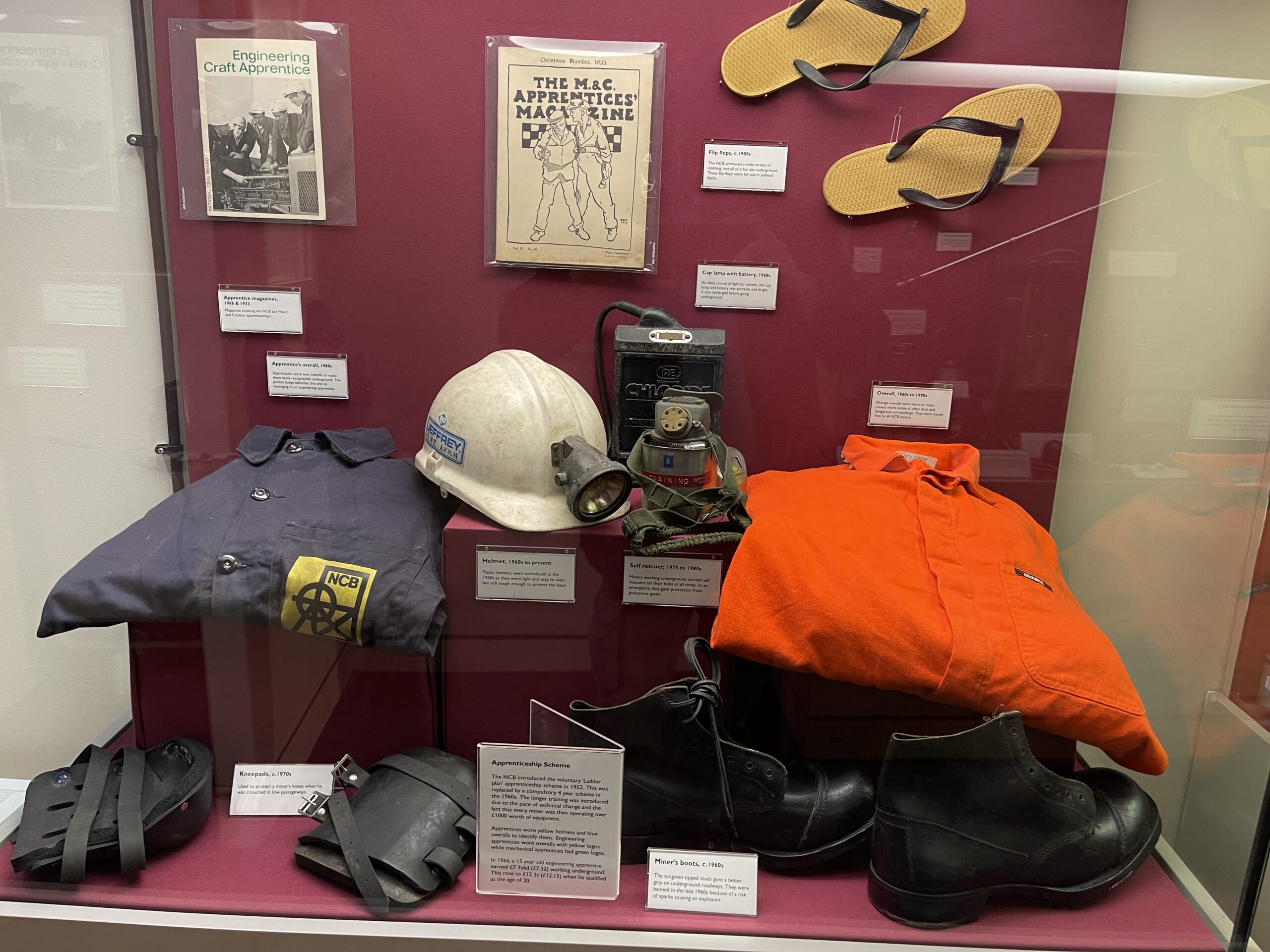

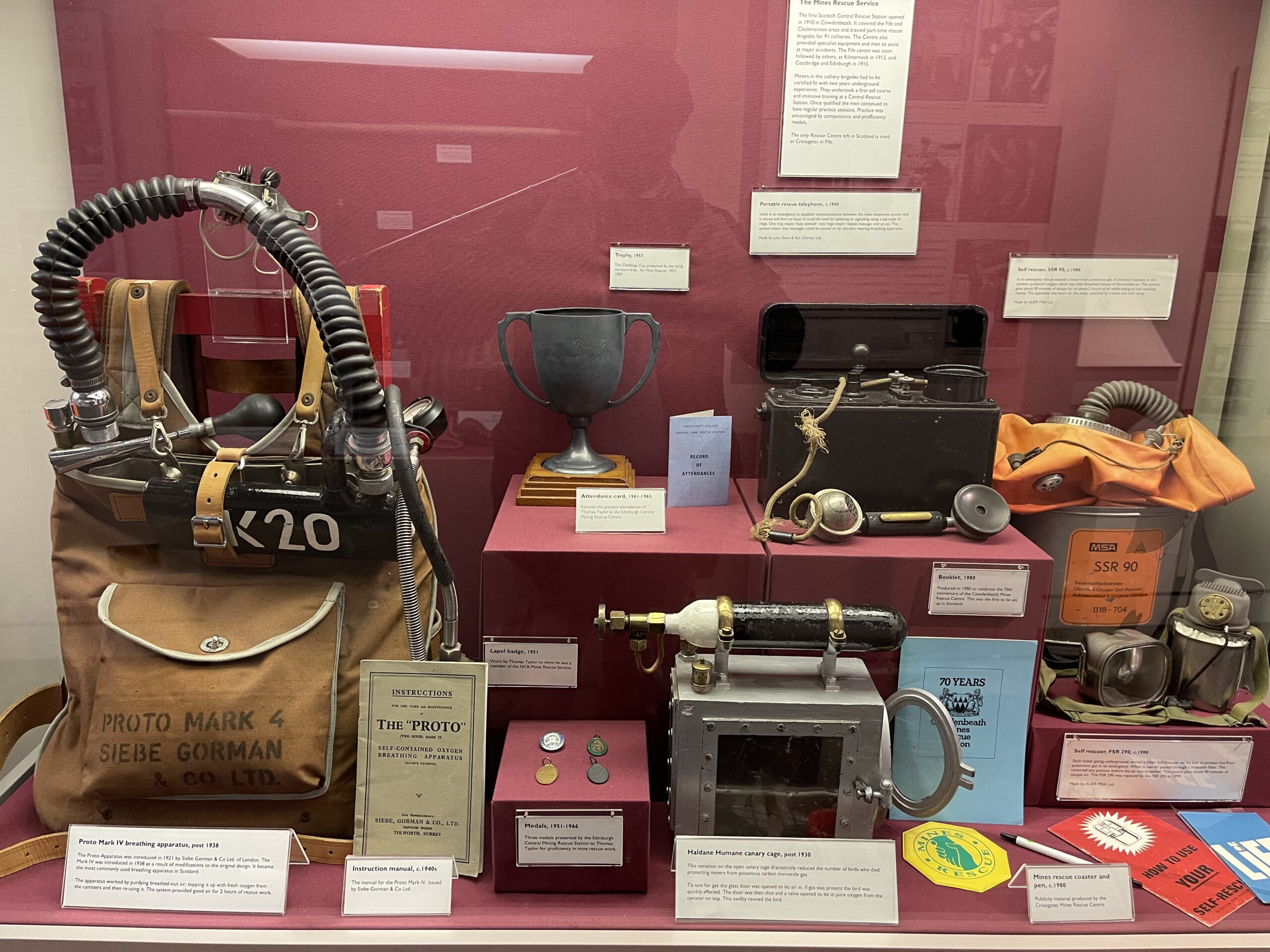

The old and new power stations had most of the machinery removed. In their place, these buildings were converted into what is now the visitor centre and exhibition spaces, both of which are fantastic. The exhibitions in particular go into great depth about the history of coal mining not just in Midlothian but throughout the UK. What makes this visitor centre so important is that younger generations would otherwise not be able to appreciate the important role that coal played in society.

It wasn’t just used to power industry and power stations, but it also heated our homes. Now as we move towards more cleaner forms of power, particularly from renewables, the use of coal and fossil fuels are anathema to contemporary thinking and policy. I’ll bet if you asked anyone under-12 what coal was used for, they would find it hard to believe that our parents and grandparents would put lumps of coal into a fireplace for heating. I can distinctly remember my mum telling me to go out to the coal bunker and fill up the coal scuttle (bucket) as the fire was low!

Tours of the Lady Victoria

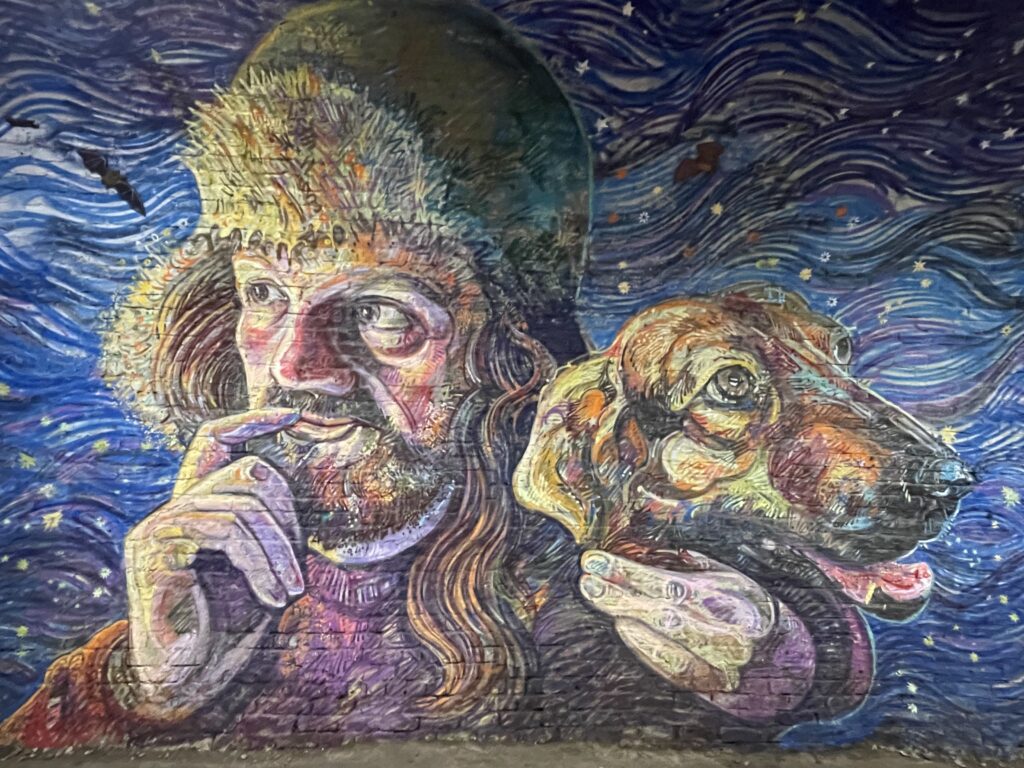

If you do decide to visit the National Mining Museum Scotland, you can either book tickets online to take a self-guided tour or a guided tour. On the self-guided tour, you will be provided with an audio tour that will guide you around the facility. Alternatively, you can book a tour with a guide who is an ex-miner. On the day that I visited, my guide was Jim Lennie who was a miner at Bilston Glen Colliery. He was fantastic and was able to give first-hand accounts of his time working in coal mining. Here’s what Jim has to say about his time as a coal miner and why it is important that today’s younger generations should visit the Museum.

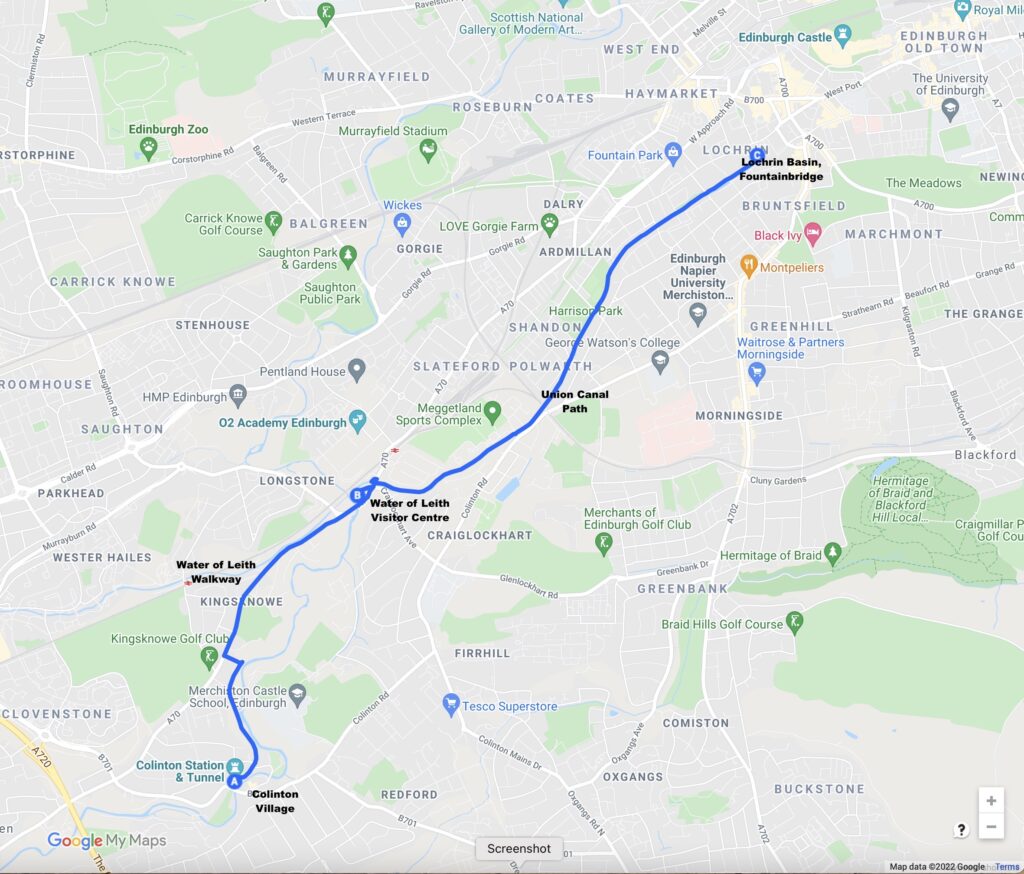

As well as visiting the National Mining Museum, why not include other fantastic sites and attractions in the surrounding area such as Rosslyn Chapel, Glenckinchie Distillery, Gilmerton Cove, Arniston House. If you are not sure about getting there under your own steam, why not check with us here at Edinburgh Cab Tours and let us build an itinerary for you or visit our Tours page for more ideas.